Educational Technology

Special education in India

The genesis of special needs education in India can be traced back to pre-independent India. There are examples in Indian history that show that people with disabilities had educational opportunities, and that disability did not come in the way of learning. Christian missionaries, in the 1880s, started schools for the disabled as charitable undertakings (Mehta, 1982). The first school for the blind was established in 1887. An institute for the deaf and mute, was set up in 1888. Services for the physically disabled were also initiated in the middle of the twentieth century. Individuals with mental retardation were the last to receive attention. The first school for the mentally challenged is established in 1934 (Mishra, 2000). Special education programmes in earlier times were, therefore, heavily dependent on voluntary initiative.

The Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) in a comprehensive report called the Sergeant Report on the post-war educational development of the country in 1944, stated provisions for the education of the handicapped , were to form an essential part of the national system of education, which was to be administered by the Education Department. According to this report, handicapped children were to be sent to special schools only when the nature and extent of their defects made this necessary. The Kothari Commission (1964–66), the first education commission of independent India, observed: “the education of the handicapped children should be an inseparable part of the education system.” The comission recommended experimentation with integrated programmes in order to bring as many children as possible into these programmes (Alur, 2002). Until the 1970s, the policy encouraged segregation. Most educators believed that children with physical, sensory, or intellectual disabilities were so different that they could not participate in the activities of a common school (Advani, 2002).

Learners with Special Educational Needs (SEN)

In India a learner with SEN is defined variously in different documents. District Primary Education Programme (DPEP) document is defined as a child with disability, namely, visual, hearing, locomotor, and intellectual (DPEP, 2001). The country report in the NCERTUNESCO regional workshop report titled Assessment of needs for Inclusive Education: Report of the First Regional Workshop for SAARC Countries (2000), states that SEN goes beyond physical disability. It also refers to, the large proportion of children—in the school age—belonging to the groups of child labour are, street children, victims of natural catastrophes and social conflicts, and those in extreme social and economic deprivation. These children constitute the bulk of dropouts from the school system (pg.58). According to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97) (UNESCO, 1997), the term Special Needs Education (SNE) means educational intervention and support designed to address SEN. The term “SNE” has come into use as a replacement for the term “Special Education”.

The earlier term was mainly understood to refer to the education of children with disabilities that takes place in special schools or institutions distinct from, and outside of, the institutions of the regular school and university system. In many countries today a large proportion of disabled children are in fact educated in institutions under the regular system. Moreover, the concept of children with SEN extends beyond those who may be included in handicapped categories to cover those who are failing in school, for a wide variety of reasons that are known to be likely impediments to a child’s optimal progress. Whether or not this more broadly defined group of children is in need of additional support, depends on the extent to which schools need to adapt their curriculum, teaching, and organisation and/or to provide additional human or material resources so as to stimulate efficient and effective learning for these pupils.

Shifting models of disability: historical progression

The shifting approaches to disability have translated into very diverse policies and practices. The various models of disability impose differing responsibilities on the States, in terms of action to be taken, and they suggest significant changes in the way disability is understood. Law, policy, programmes, and rights instruments reflect two primary approaches or discourses: disability as an individual pathology and as a social pathology. Within these two overriding paradigms, the four major identifiable formulations of disability are: the charity model, the bio-centric model, the functional model, and the human rights model.

The Charity Model

The charity approach gave birth to a model of custodial care, causing extreme isolation and the marginalisation of people with disabilities. These institutions functioned like detention centres, where persons with mental illness were kept chained, resulting in tragedies like the one at “Erwadi” in Tamil Nadu, in which more than 27 inmates of such a centre lost their lives.

The Bio-centric Model

The contemporary bio-centric model of disability regards disability as a medical or genetic condition. The implication remains that disabled persons and their families should strive for “normalisation”, through medical cures and miracles. A critical analysis of the development of the charity and bio-centric models suggests that they have grown out of the “vested interests” of professionals and the elite to keep the disabled “not educable” or declare them mentally retarded (MR) children and keep them out of the mainstream school system, thus using the special schools as a “safety valve” for mainstream schools (Tomlinson, 1982). Inclusive education offers an opportunity to restructure the entire school system, with particular reference to the curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, and above all the meaning of education (Jha, 2002).

The Functional Model

In the functional model, entitlement to rights is differentiated according to judgments of individual incapacity and the extent to which a person is perceived as being independent to exercise his/her rights. For example, a child’s right to education is dependent on whether or not the child can access the school and participate in the classroom, rather than the obligation being on the school system becoming accessible to children with disabilities.

The Human Rights Model

The human rights model positions disability as an important dimension of human culture, and it affirms that all human beings are born with certain inalienable rights. The relevant concepts in this model are:

a. Diversity

The Greek philosopher, Aristotle, once said that “things that are alike should be treated alike, whereas things that are unalike should be treated unalike in proportion to their un-alikeness.” The principle of respect for difference and acceptance of disability as part of human diversity and humanity is important, as disability is a universal feature of the human condition.

b. Breaking Down Barriers Policies that are ideologically based on the human rights model start by identifying barriers that restrict disabled persons’ participation in society. This has shifted the focus in the way environments are arranged. In education, for example, where individuals were formerly labelled as not educable, the human rights model examines the accessibility of schools in terms of both physical access (i.e., ramps, etc.) and pedagogical strategies.

c. Equality and Non-Discrimination

In international human rights law, equality is founded upon two complementary principles: nondiscrimination and reasonable differentiation. The doctrine of differentiation is of particular importance to persons with disabilities, some of who may require specialised services or support in order to be placed on a basis of equality with others. Differences of treatment between individuals are not discriminatory if they are based on “reasonable and objective justification”. Moreover, equality not only implies preventing discrimination (for example, the protection of individuals against unfavourable treatment by introducing anti-discrimination laws), but goes far beyond, in remedying discrimination. In concrete terms, it means embracing the notion of positive rights, affirmative action, and reasonable accommodation.

d. Reasonable Accommodation

It is important to recognise that reasonable accommodation is a means by which conditions for equal participation can be achieved, and it requires the burden of accommodation to be in proportion to the capacity of the entity. In the draft Comprehensive and Integral and International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities, “reasonable accommodation” has been defined as the “introduction of necessary and appropriate measures to enable a person with a disability fully to enjoy fundamental rights and freedoms and to have access without prejudice to all structures, processes, public services, goods, information, and other systems.”

e. Accessibility

The United Nations Economic and Special Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) has defined “accessibility” as “the measure or condition of things and services that can readily be reached or used (at the physical, visual, auditory and/or cognitive levels) by people including those with disabilities” (Rioux and Mohit, 2005).

f. Equal Participation and Inclusion

By focusing on the inherent dignity of the human being, the human rights model places the individual at centre stage, in all decisions affecting him/her. Thus, the human rights model, respects the autonomy and freedom of choice of the disabled, and also ensures that they, themselves, prioritise the criteria for support programmes. It requires that people with disabilities, and other individuals and institutions fundamental to society, are enabled to gain the capacity for the free interaction and participation vital to an inclusive society.

g. Private and Public Freedoms

The human rights approach to disability on the one hand requires that the States play an active role in enhancing the level of access to public freedoms, and on the other requires that the enjoyment of rights by persons with disabilities is not hampered by third-party actors in the private sphere. Educational institutions and industry, both in the public and private sectors, should ensure equitable treatment to persons with disabilities.

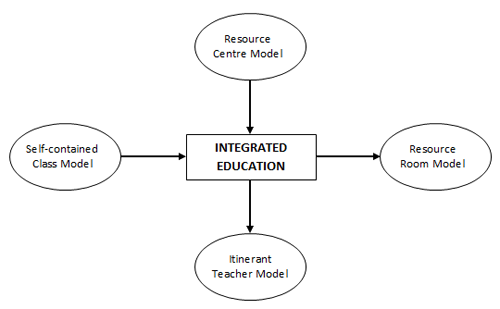

Integrated Education

In the 1970s, the government launched the Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Integrated Education for Disabled Children (IEDC). The scheme aimed at providing educational opportunities to learners with disabilities in regular schools, and to facilitate their achievement and retention. The objective was to integrate children with disabilities in the general community at all levels as equal partners to prepare them for normal development and to enable them to face life with courage and confidence. A cardinal feature of the scheme was the liaison between regular and special schools to reinforce the integration process. Meanwhile, the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) joined hands with UNICEF and launched Project Integrated Education for 6 Disabled Children (PIED) in the year 1987, to strengthen the integration of learners with disabilities into regular schools. An external evaluation of this project in 1994 showed that not only did the enrollment of learners with disabilities increase considerably, but the retention rate among disabled children was also much higher than the other children in the same blocks. In 1997 IEDC was amalgamated with other major basic education projects like the DPEP (Chadha, 2002) and the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) (Department of Elementary Education, 2000).

Inclusive Education

The National Curriculum Framework for School Education (NCFSE) (2000), brought out by the NCERT, recommended inclusive schools for all without specific reference to pupils with SEN as a way of providing quality education to all learners According to NCFSE: Segregation or isolation is good neither for learners with disabilities nor for general learners without disabilities. Societal requirement is that learners with special needs should be educated along with other learners in inclusive schools, which are cost effective and have sound pedagogical practices (NCERT, 2000) The NCFSE also recommended definitive action at the level of curriculum makers, teachers, writers of teaching–learning materials, and evaluation experts for the success of this strategy. This precipitated a revision of the IEDC scheme.

Main streaming

Mainstreaming, in the context of education, is the practice of educating students with special needs in regular classes during specific time periods based on their skills. This means regular education classes are combined with special education classes. Schools that practice mainstream believe that students with special needs who cannot function in a regular classroom to a certain extent belong in the special education environment.[2]

Access to a special education classroom, often called a “self-contained classroom or resource room”, is valuable to the student with a disability. Students have the ability to work one-to-one with special education teachers, addressing any need for remediation during the school day. Many researchers, educators and parents have advocated the importance of these classrooms amongst political environments that favor their elimination.

Instructional strategies

Different instructional techniques are used for some students with special educational needs. Instructional strategies are classified as being either accommodations or modifications.

An accommodation is a reasonable adjustment to teaching practices so that the student learns the same material, but in a format that is more accessible to the student. Accommodations may be classified by whether they change the presentation, response, setting, or scheduling of lessons. For example, the school may accommodate a student with visual impairments by providing a large-print textbook. This is a presentation accommodation.

A modification changes or adapts the material to make it simpler.[33] Modifications may change what is learned, how difficult the material is, what level of mastery the student is expected to achieve, whether and how the student is assessed, or any another aspect of the curriculum.[34] For example, the school may modify a reading assignment for a student with reading difficulties by substituting a shorter, easier book. A student may receive both accommodations and modifications.

Examples of modifications

- Skipping subjects: Students may be taught less information than typical students, skipping over material that the school deems inappropriate for the student’s abilities or less important than other subjects. For example, students with poor fine motor skills may be taught to print block letters, but not cursive handwriting.

- Simplified assignments: Students may read the same literature as their peers but have a simpler version, such as Shakespeare with both the original text and a modern paraphrase available.

- Shorter assignments: Students may do shorter homework assignments or take shorter, more concentrated tests.

- Extra aids: If students have deficiencies in working memory, a list of vocabulary words, called a word bank, can be provided during tests, to reduce lack of recall and increase chances of comprehension. Students might use a calculator when other students do not.

- Extended time: Students with a slower processing speed may benefit from extended time for assignments and/or tests in order to have more time to comprehend questions, recall information, and synthesize knowledge.

- Students can be offered a flexible setting in which to take tests. These settings can be a new location to provide for minimal distractions.

Examples of accommodations

- Response accommodations:Typing homework assignments rather than hand-writing them (considered a modification if the subject is learning to write by hand). Having someone else write down answers given verbally.

- Presentation accommodations: Examples include listening to audiobooks rather than reading printed books. These may be used as substitutes for the text, or as supplements intended to improve the students’ reading fluency and phonetic skills. Similar options include designating a person to read to the student, or providing text to speech software. This is considered a modification if the purpose of the assignment is reading skills acquisition. Other presentation accommodations may include designating a person to take notes during lectures or using a talking calculator rather than one with only a visual display.

- Setting accommodations:Taking a test in a quieter room. Moving the class to a room that is physically accessible, e.g., on the first floor of a building or near an elevator. Arranging seating assignments to benefit the student, e.g., by sitting at the front of the classroom.

- Scheduling accommodations: Students may be given rest breaks or extended time on tests (may be considered a modification, if speed is a factor in the test). Use a timer to help with time management.

Report on inclusive model in India

UNICEF’s Report on the Status of Disability in India 2000 states that there are around 30 million children in India suffering from some form of disability. The Sixth All-India Educational Survey (NCERT, 1998) reports that of India’s 200 million school-aged children (6–14 years), 20 million require special needs education. While the national average for gross enrolment in school is over 90 per cent, less than five per cent of children with disabilities are in school. A study was conducted by UNICEF to analyse the global polices in education of children with disabilities and how India’s policies and programme align with them. The following key observations are reported and recommendations were made for future strategies.

Key observations

Based on analysis of the state of special and inclusive education and the documentation of inclusive model practices, the following key observations are made.

Central and state governments have taken a number of initiatives to improve the enrolment, retention and achievement of children with disabilities. There is a need to establish interlinks and collaborations among various organizations to prevent overlapping, duplication and contradictions in programme implementation.

Most services for children with disabilities are concentrated in big cities or close to district headquarters. The majority of children with disabilities who live in rural areas do not benefit from these services.

There is an absence of consistent data on the magnitude and educational status of children with disabilities, and the disparities between regions and types of disability. This makes it difficult to understand the nature of the problem, and to make realistic interventions.

Special schools and integrated educational practices for children with disabilities have developed over the years. Inclusive educational has gained momentum over the last decade.

Community involvement and partnerships between government agencies and NGOs have been instrumental in promoting inclusive education.

Many schools have a large number of children in each classroom and few teachers. As a consequence of this, many teachers are reluctant to work with children with disabilities. They consider it an additional workload.

Training for sensitization towards disability and inclusion issues, and how to converge efforts for effective implementation of programmes, are important concerns.

Different disabilities require different supports. The number of skilled and trained personnel for supporting inclusive practices is not adequate to meet the needs of different types of disability.

The curriculum lacks the required flexibility to cater to the needs of children with disabilities. There are limited developmentally appropriate teaching–learning materials for children both with and without disabilities. The teaching–learning process addresses the individual learning needs of children in a limited way.

Families do not have enough information about their child’s particular disability, its effects and its impact on their child’s capacity. This often leads to a sense of hopelessness. Early identification and intervention initiatives sensitize parents and community members about the education of children with disabilities.

Recommendations

Bearing in mind this scenario, the following recommendations need to be considered in order to move towards education of children with disabilities in inclusive settings.

The attitude that ‘inclusive education is not an alternative but an inevitability, if the dream of providing basic education to all children is to ever become a reality’ needs to be cultivated among all concerned professionals, grassroots workers, teachers and community members, especially in rural and remote areas.

Links and bridges need to be built between special schools and inclusive education practices. Linkages also need to be established between community-based rehabilitation programmes and inclusive education.

Public policies, supportive legislation and budgetary allocations should not be based on incidence, but on prevalence of special education needs, and take into consideration the backlog created as a result of decades of neglect.

The existing dual ministry responsibilities should be changed. Education of children with disabilities should be the responsibility of the Department of Education. The Ministry of Welfare should confine itself to support activities only.

Inclusion without ‘adequate’ preparation of general schools will not yield satisfactory results. It is essential that issues related to infrastructural facilities, curriculum modification and educational materials should be addressed.

Regular evaluation should be based on performance indicators specified in the implementation programme, and accountability for effective implementation at all levels should be ensured.

There should be emphasis on bottom-up, school-based interventions as part of regular education programmes following inclusive strategies. The programme should be based on stakeholder participation, community mobilization, and mobilization of NGO, private and government resources.

The training of general teachers at pre-service and in-service levels should address the issue of education of children with disabilities, so that teachers are better equipped to work in an inclusive environment. Some of the issues in training that need to be addressed include the methodology to be adopted for identifying children with disabilities; classroom management; use of appropriate teaching methodologies; skills for adapting the curriculum; development of teaching–learning materials that are multi-sensory in nature; evaluation of learning; etc. The time has come to scale up successful experiments on teacher training such as the Multi-site Action Research Project and the Indian adaptation of the UNESCO Teacher Education Resource Pack, since these experiences are lying dormant.

Orientation training of policy-makers and education department officials, both at the state and block level, is essential. In addition, there is a need to develop on-site support systems for teachers. Grassroots workers, parents, special school teachers, para-teachers and other individuals can be shown how to provide the required support.

The existing handful of teacher trainers cannot reach the vast number of teachers working with children with disabilities in rural/remote areas. There is a need to explore alternatives such as training para-teachers, investing in pilot studies to develop tele-rehabilitation programmes, and exploring strategies for distance education.

The preparation of children—in the form of early childhood intervention before enrolment—is required. This would ensure that they do not drop out, are retained in schools, and compete equally with other children.

In order to strengthen inclusive practices, networking between existing practitioners (i.e., IEDC, DPEP, SSA, etc.) would be useful. Simultaneous implementation, and consistent monitoring, reinforcement and coordination between government departments and NGOs at national and state levels will promote inclusive practices.

References

NCERT (2006), National focus group on education of children with special needs, Publications department, NCERT, New Delhi.

Examples of Inclusive Education India Unicef Regional Office for South Asia P.O. Box 5815, Lekhnath Marg Kathmandu, Nepal.

E-mail: rosa@unicef.org www.unicef.org/rosa/InclusiveInd.pdf

Assignment

- Visit any special school and present detailed report.

- Critically analyse the efforts of Sarva Siksha Abhiyaan in the promotion of Special education.